Christina Sterbenz

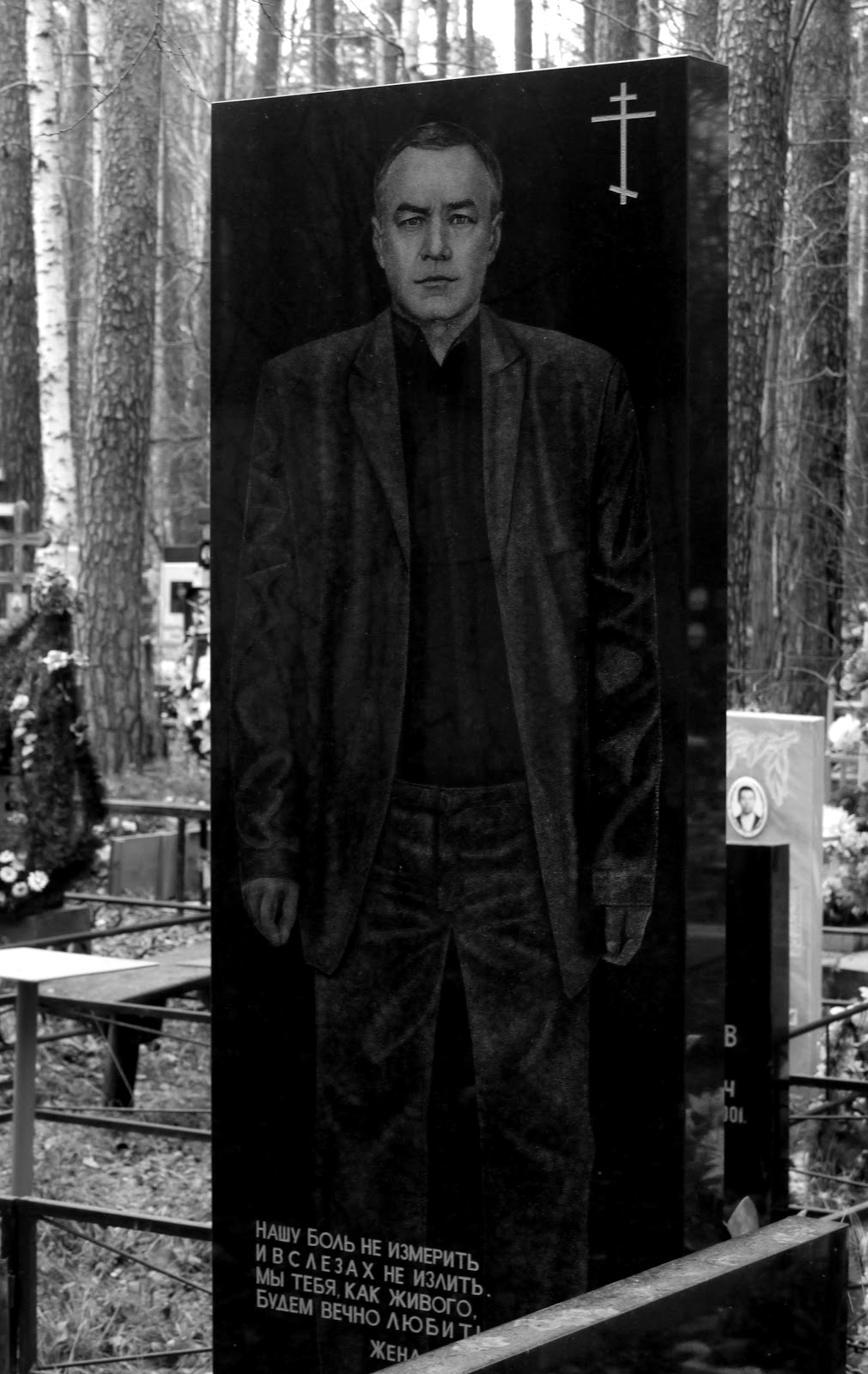

Semion MogilovichFBISemion Mogilevich, a known Russian mob boss

Drug trafficking, trading nuclear material, contract murders, and international prostitution — that's how the Federal Bureau of Investigation believes Semion Mogilevich, one of its top 10 most wanted fugitives, has spent his time over the last few decades.

Indicted in 2003 for countless fraud charges, Mogilevich now primarily lives in Moscow. His location allows him to maintain close ties to the Bratva, or The Brotherhood, aka the Russian mob.

The 'Boss Of Bosses'

A 5'6" and a portly chain smoker, Mogilevich is known as "boss of bosses" in one of the biggest mafia states in the world.

Born in 1946 in Kiev, Ukraine, Mogilevich once acted as the key money laundering contact for the Solntsevskaya Bratva, a super-gang based in Moscow. He has since held over 100 front companies and bank accounts in 27 different countries, all to keep the cash flowing.

In 1998, the FBI released a report naming Mogilevich as the leader of an organization with about 250 members. Only in operation only four years, the group's main activities included arms dealing, trading nuclear material, prostitution, drug trafficking, oil deals, and money laundering.

Between 1993 and 1998, however, Mogilevich caught the FBI's attention when he allegedly participated in a $150 million scheme to defraud thousands of investors in a Canadian company, YBM Magnex, based just outside Philadelphia, which supposedly made magnets. With his economics degree and clever lies, Mogilevich forged documents for the Securities and Exchange Commission that raised the company's stock price nearly 2,000%.

When asked about YBM by BBC in 2007, Mogilevich replied: "Well if they found old-fashioned hanky panky [i.e., suspicious activity], it's up to them to prove it. Unfortunately, I don't have access to FBI files."

"What makes him so dangerous is that he operates without borders," said Special Agent Peter Kowenhoven, who has worked on Mogilevich's case since 1997. "Here’s a guy who managed to defraud investors out of $150 million without ever stepping foot in the Philadelphia area."

In 1998, the Village Voice reported on hundreds of previously classified FBI and Israeli intelligence documents. They placed Mogilevich, also known as "Brainy Don," as the leader of the Red Mafia, a notorious Russian mob family infamous for its brutality. Based in Budapest, members held key posts in New York, Pennsylvania, Southern California, and even New Zealand.

"He's the most powerful mobster in the world," Monya Elison, one of Mogilevich's partners in a prostitution ring, told the Voice. He claimed he's Mogilevich's best friend.

Geopolitical Influence

Arguably one of Mogelivich's most concerning characteristics is his influence in Europe's energy sector. With only a $100,000 bounty on his head, he controls extensive natural gas pipelines in Russia and Eastern Europe.

Right now, Russia supplies about 30% of Europe's gas. Ironically, the country's largest pipeline to the rest of Europe shares a name with the mob — Bratstvo.

Europe Gas

John Wood, a senior anti-money laundering consultant at IPSA International wrote an entire report on Mogelivich. According to his research, the Ukrainian-born Russian mobster had long planned his stake in Europe's gas.

In 1991, Mogilevich started meddling in the energy sector with Arbat International. For the next five years, the company served as his primary import-export petroleum company. Then, in 2002, an Israeli lawyer named Zeev Gordon, who represented Mogilevich for more than 20 years, created Eural Trans Gas (ETG), the main intermediary between Turkmenistan and Ukraine. Some reports show that Gordon registered the company in Ukrainian oligarch Dmitry Firtash's name.

After that, Russia’s energy giant Gazprom and Ukraine's Centragas Holding AG teamed up to establish Swiss-registered RosUkrEnergo (RUE) to replace ETG. Firtash and Gazprom reportedly roughly split the ownership of RUE.

In 2010, however, then prime minister of Ukraine, Yulia Tymoshenko, said she had "documented proof that some powerful criminal structures are behind the RosUkrEnergo (RUE) company," according to WikiLeaks. Even before, the press had widely speculated about Mogilevich's ties to RUE.

Dmitry FirtashReutersDmytro Firtash, one of Ukraine's richest men, (R) and Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich take part in an opening ceremony of a new complex for the production of sulfuric acid in Crimea region in April 2012.

Although Firtash has repeatedly denied having any close relationship with Mogilevich, he has admitted to asking permission from the mobster before conducting business in Ukraine as early as 1986, Reuters recently reported. At the request of the FBI, Firtash was arrested in Austria for suspicion of bribery and creating a criminal organization.

Mogilevich may even have a working relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to a published conversation between Leonid Derkach, the former chief of the Ukrainian security service, and former Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma.

"He's [Mogilevich] on good terms with Putin," Derkach reportedly said. "He and Putin have been in contact since Putin was still in Leningrad."

A Free Man

In 2007, Mogelivich told BBC that his business was selling wheat and grain.

In 2008, however, Russian police arrested Mogelivich, using one of his many pseudonyms, Sergei Schneider, in connection with tax evasion for a cosmetics company, Arbat Prestige. Mogilevich ran that company with his partner, Vladimir Nekrosov. Three years later, the charges were dropped.

Considering the US doesn't have an extradition treaty with Russia, as long as Mogilevich stays within Putin's borders, the "boss of bosses" will likely remain a free man. He's believed to have Russian, Israeli, Ukrainian, and Greek passports.